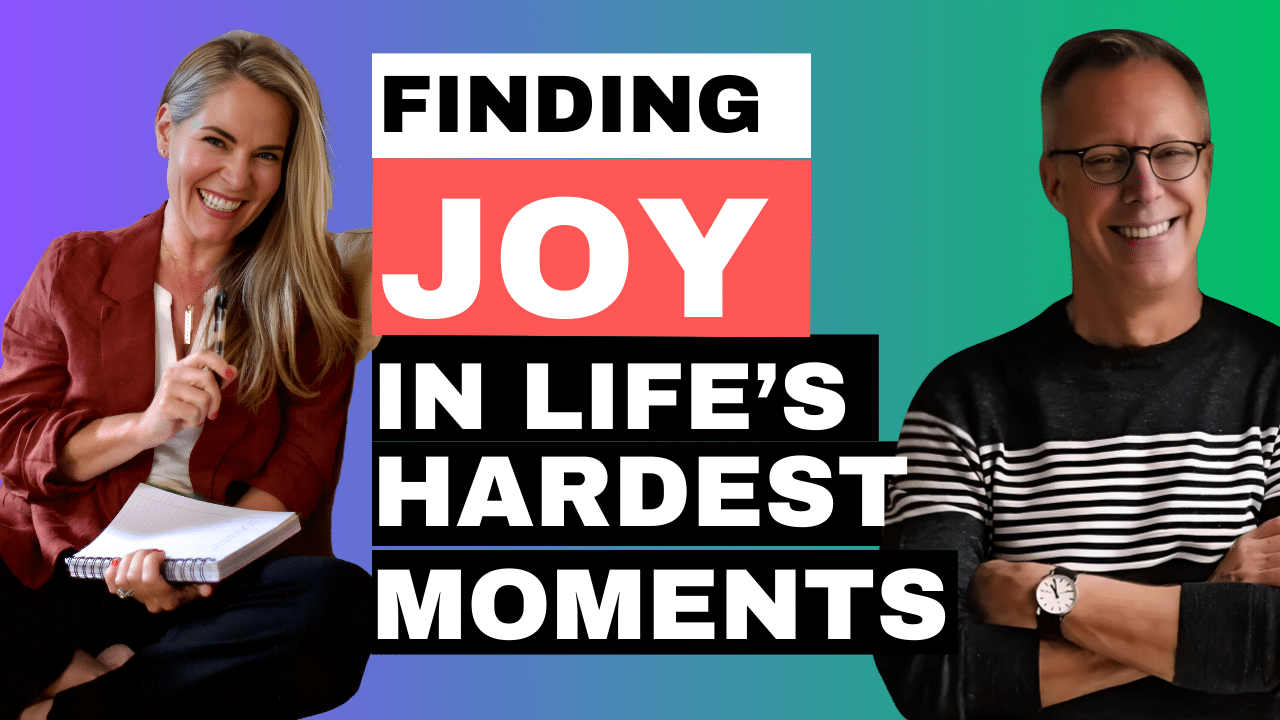

Here’s a Peek Inside the Episode:

- [01:54] Why a Book on Joy?

- Steven shares the personal and professional reasons that led him to write about joy. After experiencing profound loss in 2017—losing both parents, a marriage, and supporting his sister through a cancer diagnosis—he sought light in the darkness. What started as a small joy project on social media grew into a larger exploration of how we create and share joy.

- [06:45] The Pecan Pie Competition & Joy of Storytelling

- Steven recounts a humorous and heartfelt family story about how storytelling—not just a good recipe—makes traditions meaningful and joyful.

- [09:22] The Difference Between Happiness and Joy

- Many people conflate happiness with joy, but Steven breaks down how joy is more of a state of being rather than a reaction to external circumstances. Joy is deeply tied to community, connection, and perspective.

- [12:50] Why We Struggle to Allow Ourselves Joy

- Steven shares that many people feel undeserving of joy due to personal hardship or societal challenges. However, he highlights how joy can coexist with grief, loss, and struggle.

- [17:22] Joy and Resilience

- How marginalized communities—including Black and LGBTQ+ communities—have cultivated joy as an act of resilience and resistance. Steven and Regina discuss how traditions and community rituals create lasting joy even in hardship.

- [24:37] Embracing Imperfection

- Steven opens up about his journey of accepting his body, from scars to a slightly off-center nose, and how embracing imperfections has led to greater self-acceptance and joy.

- [29:58] The Bond Between Siblings & Honoring Loss

- Steven shares a moving story about coming out to his sister Julie, her joyful reaction, and the deep sibling bond they shared throughout life.

- [32:00] Medical Aid in Dying: Julie’s Choice

- Steven reflects on his sister Julie’s decision to pursue medical aid in dying (MAID) and how their family navigated this process. He discusses the importance of choice, dignity, and supporting a loved one through their end-of-life journey.

- [38:12] Joy Amidst Grief

- Steven shares how his family celebrated Julie’s life with a joyful birthday and farewell party, demonstrating how joy and sorrow can exist together.

- [39:23] A Simple Call to Action for Joy

- Advice for listeners: Every night before you go to sleep, reflect on one moment that brought you joy that day—even on the hardest days.

Resources Mentioned:

About Steven Petrow

Steven Petrow is an award-winning journalist and book author who is best known for his Washington Post and New York Times essays on aging, health, and civility. Steven’s 2019 TED Talk, “3 Ways to Practice Civility” has been viewed nearly two million times and translated into 16 languages.

Steven’s new book, The Joy You Make, was published in 2024 by The Open Field, Maria Shriver’s personally curated imprint at Penguin Random House. His last book, Stupid Things I Won’t Do When I Get Old, was published in 2021 and named one of the New York Times’ “favorite” books of the year (among other accolades).

He’s also the author of Steven Petrow’s Complete Gay & Lesbian Manners and The Lost Hamptons. He’s a much sought-after public speaker, and you’re likely to hear him when you stream NPR or one of your favorite — or least favorite — TV networks. He’s a past president of NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists and a current board member at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Steven is also the 2024 North Carolina Piedmont Laureate and lives in Hillsborough, N.C.

Follow Steven on Twitter at @StevenPetrow and on Instagram @mr.steven.petrow; “Like” him on Facebook.